Match of the Century: Fischer and Spassky

One of the most remarkable match in history of chess between Fischer and Spassky.

.jpg)

Scene from the 1972 World Championship in Reykjavik. The Cold War backdrop gave the 1972 World Chess Championship between American challenger Bobby Fischer and Soviet champion Boris Spassky an epic significance. The Soviet Union had dominated world chess for 24 years straight, producing an unbroken chain of champions since 1948.

Now an eccentric 29-year-old American genius was challenging that hegemony. The match was widely dubbed the “Match of the Century,” and its East-vs.-West narrative sparked unprecedented media coverage and public interest in chess.

Henry Kissinger, then U.S. National Security Advisor, even phoned Fischer urging him to play, joking, “This is the worst chess player in the world calling the best chess player in the world.” Such was the political and cultural weight of the encounter, with both champions perceived as products of their respective ideologies.

Players’ Styles and Preparation

Fischer came into the match on a historic hot streak, having crushed elite grandmasters in the Candidates matches by unheard-of margins. He was a fierce perfectionist known for meticulous opening preparation and relentless will to win.

Spassky, the reigning champion, was an all-around stylist – dynamic and tactical when needed, but also comfortable in quiet positional play. The Soviet chess establishment took Fischer so seriously that a team of their best analysts (grandmasters like Tal, Petrosian, Smyslov, etc.) collaborated to study Fischer’s games in depth. They produced confidential reports identifying perceived weaknesses in Fischer’s play (for example, that Fischer avoided closed positional games).

Fischer, for his part, prepared largely alone – famously poring over a collection of Spassky’s games and making his own notes. By the match’s start, the entire Soviet chess apparatus was effectively working to support Spassky, while Fischer relied on his unparalleled focus and a few helpers.

Match Drama and Key Turning Points

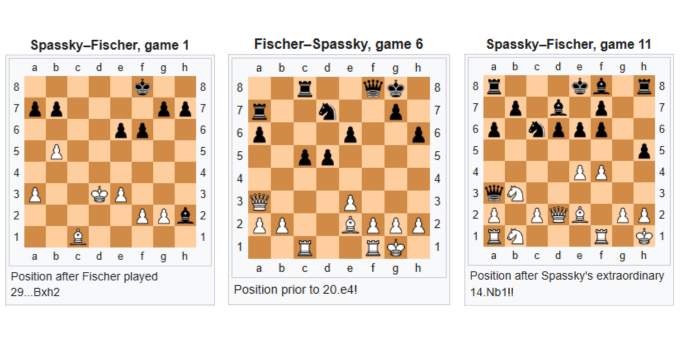

The match began inauspiciously for Fischer. In Game 1, he made an infamous blunder attempting to snatch a “poisoned pawn,” losing a bishop and eventually the game. Then Fischer forfeited Game 2 after a dispute over camera noise, falling behind 0–2. This rocky start nearly derailed the match, but behind the scenes appeals (including Kissinger’s call and Spassky’s own willingness to continue despite Soviet orders to return home) kept it on track.

With the score 0–2, Fischer was “playing a game of psychological warfare” – his extreme demands and antics seemingly aimed at unsettling the “unflappable” Spassky. Remarkably, the strategy seemed to work. The match resumed in a private room with no cameras, and in Game 3 Fischer stunned Spassky with a bold opening novelty to score his first ever win against him. That victory buoyed Fischer’s confidence and shifted the momentum.

Fischer proceeded to win Games 5 and 6, showcasing his brilliance. Game 6 in particular — a strategic masterpiece in which Fischer, playing 1.c4 as White, slowly outmaneuvered Spassky — prompted Spassky to join the audience in applauding Fischer’s play at its conclusion, an extraordinary display of sportsmanship.

By mid-match, Fischer had overtaken Spassky on the scoreboard. Spassky fought back with a notable win in Game 11, unveiling a well-prepared innovation in Fischer’s beloved Sicilian Najdorf opening that caught Fischer off guard.

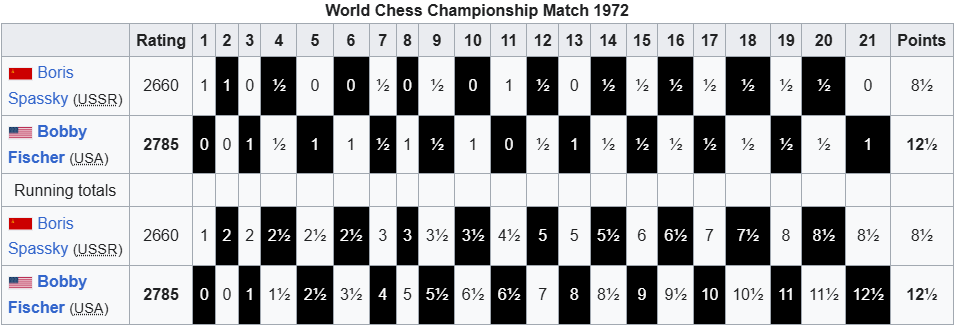

However, Fischer’s lead was never seriously threatened. A crucial moment came in Game 13, a long seesaw battle which Spassky could have drawn but for a late endgame blunder, allowing Fischer to notch another win. After that, a string of hard-fought draws followed, interspersed with one final Fischer victory in Game 21.

Notable Moves and Strategies

Throughout the match, Fischer demonstrated his versatility. He deviated from his usual 1.e4 openings to throw Spassky off, and showed he could outplay the champion in both tactical melees and quiet positional fights.

Spassky’s team had banked on Fischer being uncomfortable in closed positions, but Fischer proved them wrong by winning in varied pawn structures (for example, a closed Pirc Defense in Game 5 and an endgame grind in Game 13).

One of the most famous moves came in Game 1 — Fischer’s ill-fated 29…Bxh2, grabbing a pawn and getting his bishop trapped, a lapse that cost him the game. In contrast, Game 6 featured Fischer’s brilliant 22.Nxh7!! knight sacrifice (in a complex middlegame) that unraveled Spassky’s defenses, often cited as the coup de grâce of that “perfect game.”

Spassky, for his part, showed imaginative sparks as well, such as the surprise 14.Nb1!! retreat in Game 11’s Poisoned Pawn Sicilian, a move that shocked commentators at the time and ultimately led to his last victory.

Outcome and Impact

Fischer clinched the title when Spassky resigned at adjournment of Game 21, closing the match with a score of 12½–8½ (Fischer won 7 games to Spassky’s 3, with 11 draws; one of Spassky’s wins was the forfeit).

Fischer became the 11th World Chess Champion – the first American-born champion – ending the Soviets’ long monopoly. The significance of the result was enormous. In the chess world, it was a seismic upset against the mighty Soviet chess school. Culturally, it turned Fischer into a Cold War-era icon; the chess boom that followed saw newfound interest in the game worldwide.

In the West, especially the United States, millions followed the match on television and newspaper front pages, and chess sets reportedly sold out in stores as people were inspired to play. As GM Jan Timman later recalled, “everybody wanted to play. … If I had any doubts about becoming a chess professional, they faded away after the match in Reykjavik.”. Chess had never before been so mainstream.

However, Fischer’s victory was short-lived in impact – he famously refused to defend his title in 1975 and withdrew from competitive chess, ceding the championship back to the Soviets (Anatoly Karpov) by default. Yet the 1972 Fischer–Spassky match remains the most famous chess match in history, a symbol of chess as proxy battle between rival world powers and a personal duel of mythic intensity. It elevated the profile of chess globally and left a legacy that still fascinates enthusiasts 50 years later.

Conclusion

This chess match left an indelible mark on chess history. Fischer’s victory over Spassky broke geopolitical barriers and sparked a worldwide chess boom. Fischer’s triumph not only ended Soviet dominance but also sparked a global chess boom, demonstrating how deep preparation, psychological pressure, and strategic versatility could redefine the limits of competitive play.

Chess enthusiasts still pore over the games from that match move by move, finding new insights and appreciating the layers of strategy. It remind us that chess, at its best, is not just a game or sport but a theater of ideas and wills. Iconic one-on-one chess matches like this one continue to inspire new generations of players and fans, and they stand as timeless testaments to the richness of chess history.